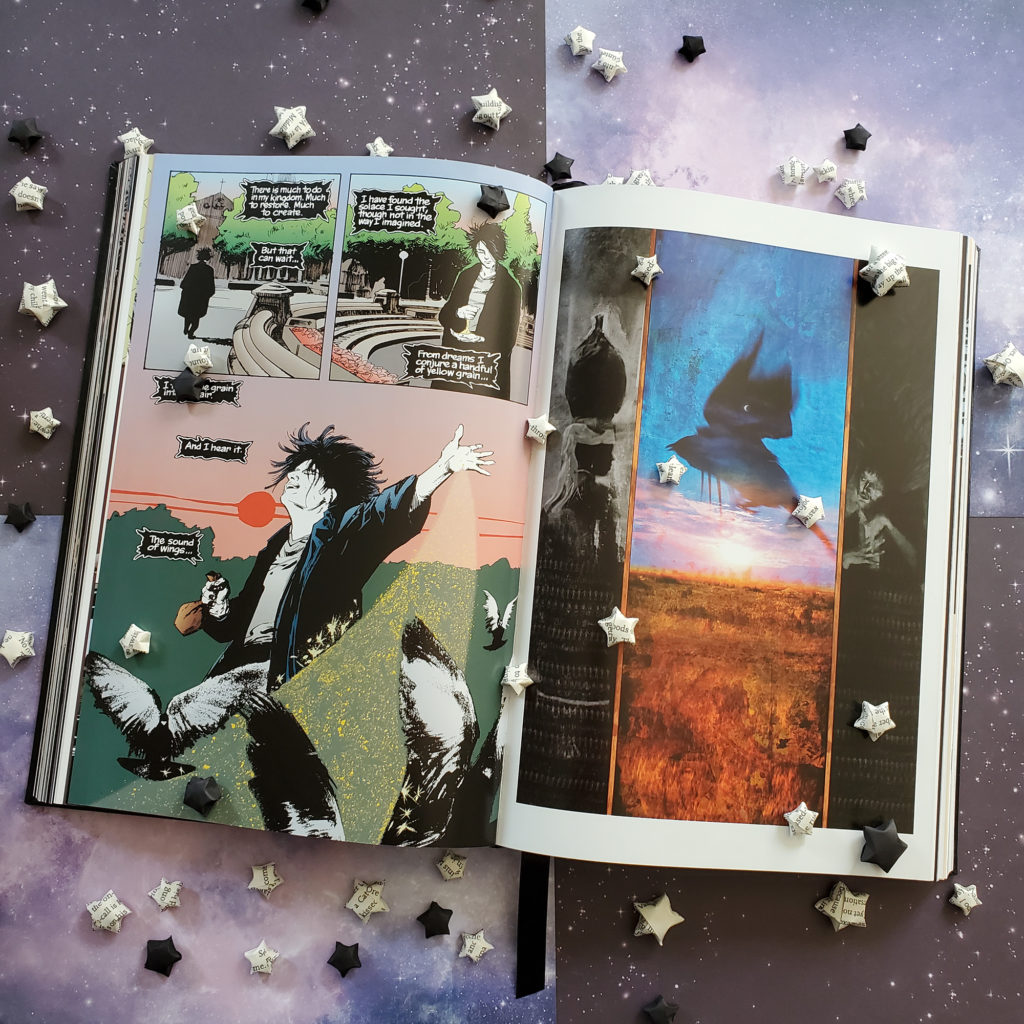

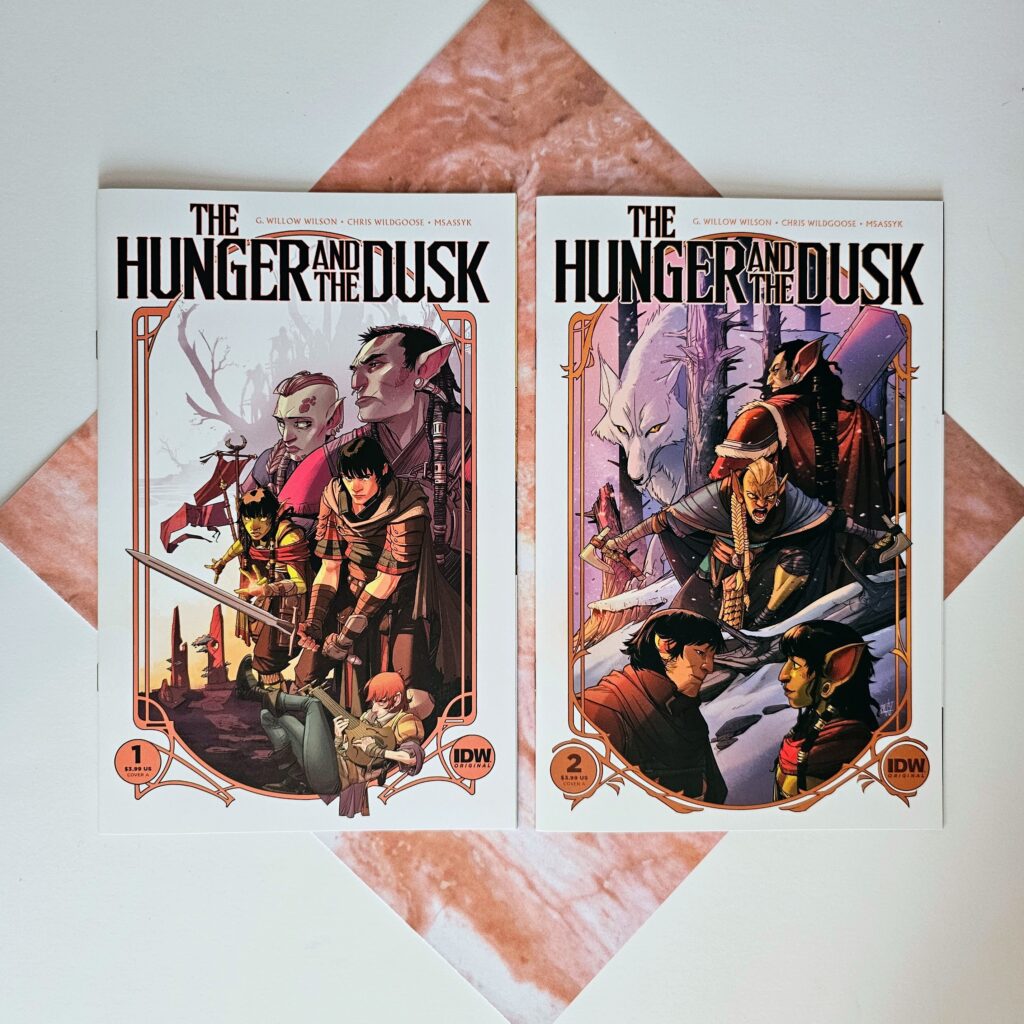

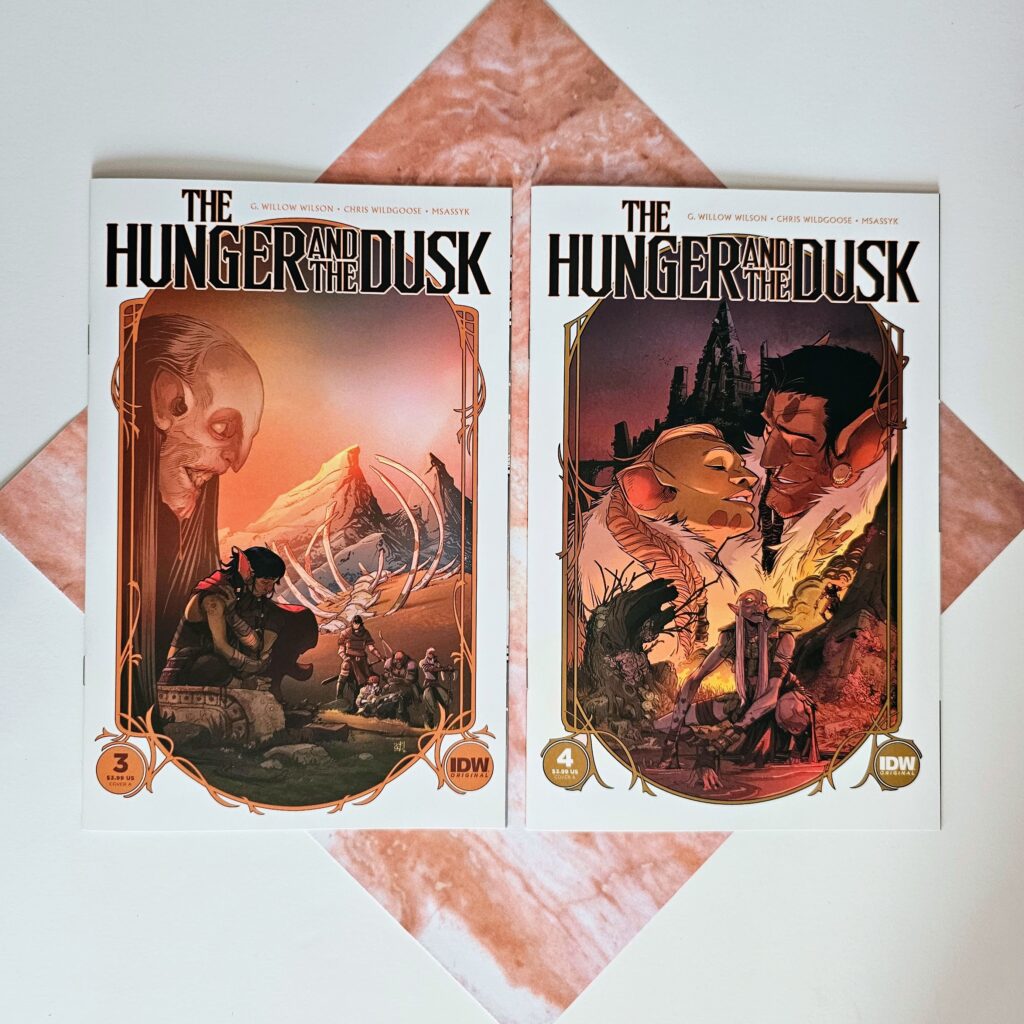

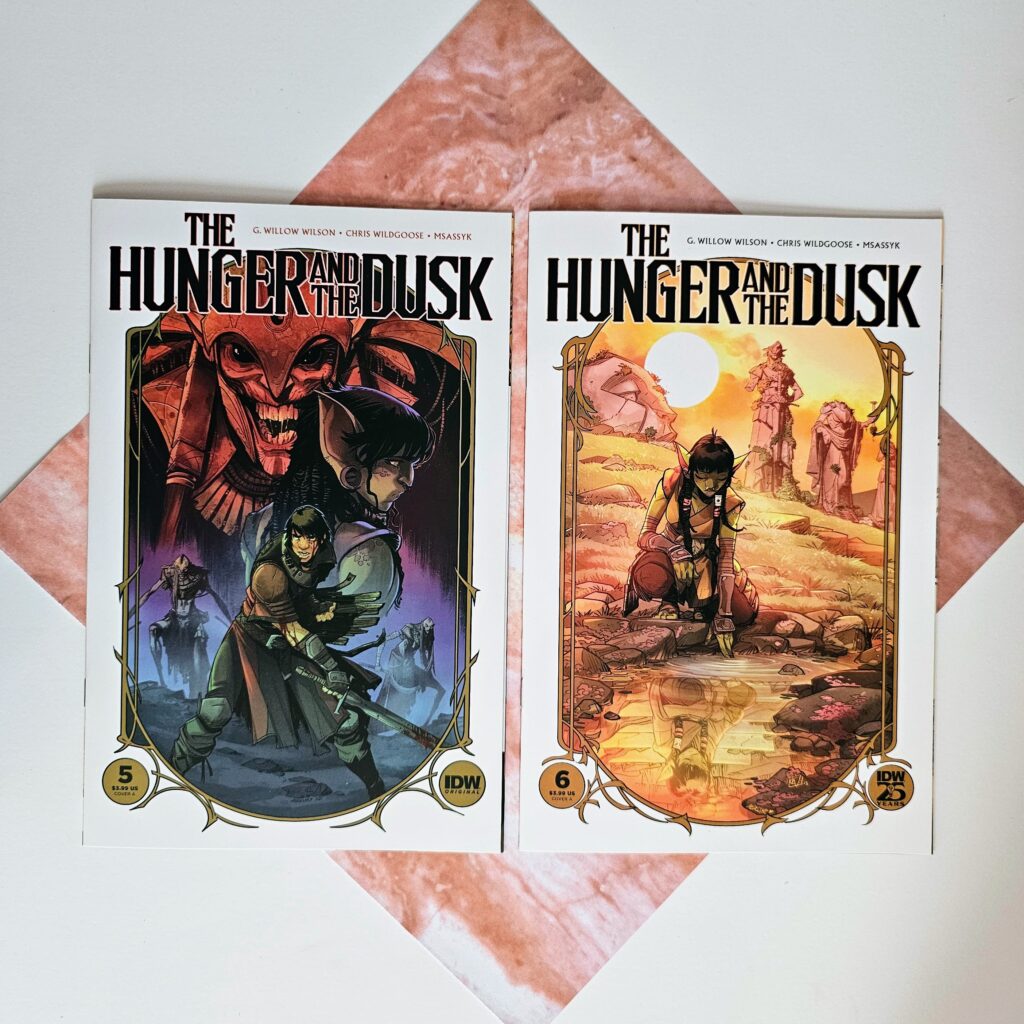

The Hunger and the Dusk, written by G. Willow Wilson and illustrated by Chris Wildgoose, is a high fantasy comic series tinted with horror. I’ve been reading this one monthly since its debut in July 2023, and it’s been a highlight of my pull list. Clearly, this review is long overdue!

Volume one collects the first six issues, and there’s a lot of ground to cover! The first story arc ended on a cliffhanger, but thankfully the first issue of book two came out last month. I’m not going to cover that in this review, but I’m sure I’ll be yelling about the series as issues come out over on Threads.

This post contains affiliate links to Bookshop.org, an online bookstore that financially supports independent bookstores.

The Hunger and the Dusk: A Spoiler-Free Overview

When vicious, mysterious raiders known as the Vangol return to the dying world they left behind hundreds of years ago, humans and orcs must form an alliance to fight the invaders before it’s too late for both races. Overcoming centuries of fighting and racism is no small task, though. A tenuous treaty is all that keeps orcs and humans from slaughtering each other over increasingly small amounts of fertile land.

As part of the treaty, the orcs send one of their best healers, Gruakhtar Icemane—Tara to her friends—to travel with the mercenary group Last Men Standing. Led by Cal Battlechild, the Last Men set off to face the Vangol with their new member.

Tara and Cal form an uneasy, tentative friendship. When a surprise Vangol attack leaves one of the Last Men dead, both Tara and Cal blame themselves. They begin to open up to each other, hinting at a possible future romance.

But the Last Men don’t have long before they catch a Vangol scout scoping out their camp. The discovery of the scout sets off a chain of events that test Tara and Cal’s burgeoning relationship, along with the entire treaty.

All the while, the Vangol creep further inland, threatening annihilation of humans and orcs alike. . .

If Only Things Were Simple

The Hunger and the Dusk primarily follows Tara’s point of view, with some scenes following her cousin Troth. (Tara and Troth were supposed to marry until he unexpectedly became overlord of the Icemane clan). Stories with orc points of view are becoming more common, and while a greater discussion of the rehabilitation/reclamation of the orc image is beyond the scope of this review, I greatly enjoy the way Wilson and Wildgoose handle it.

While we do have scenes of the humans of Last Men Standing starting to deal with their own implicit biases (the bard realizes he has to write all new songs because all the ones he knows trash talk the orcs), the story sticks pretty close to Tara’s and Troth’s points of views.

These orcs are not vicious, mindless violence machines as they are often portrayed in high fantasy. Tara, in fact, is quite the opposite with her powerful healing ability. Her cousin Troth is portrayed as a wise, strong leader who is forced to make personal sacrifices for the good of his people. Troth’s new bride, Faran, is whip-smart and invested in peace between humans and orcs.

Some of the best scenes in the book show Troth and Faran getting to know each other. Their interactions are tender and real, even though their marriage begins as a political one. (I also appreciate that we see Faran initiating sex—Troth clearly respects her boundaries.)

The Vangol

I’d be remiss to write a review of The Hunger and the Dusk without dedicating some time to the villains. The Vangol are quick, sneaky, and deadly. The first scene in issue one establishes that everyone is terrified of them.

Gaunt and pale with elongated torsos and limbs, the Vangol remind me somewhat of the vampires from 30 Days of Night. They carry the same sense of quick-moving, unavoidable dread. Indeed, the book’s title derives from the Vangol’s tendency to attack at dusk.

The first six issues of the comic give us more questions than answers when it comes to these ghoul-like people. All we know is that at some point in the distant past, they lived on the same continent as humans, orcs, dwarves, and elves. The Vangol left, and the dwarves and elves died out (thought not necessarily in that order). No one knows why they’ve returned, but it seems it may have something to do with the land slowly dying.

The sense of mystery surrounding the Vangol, along with their uncanny appearance and demonstrated viciousness, makes them a compelling antagonist. They are an existential threat to both groups in the truest sense of the word. If humans and orcs fail to stop the Vangol, they will join the dwarves and elves in extinction.

The Hunger and the Dusk One-Sentence Review

The Hunger and the Dusk offers a fresh take on familiar fantasy tropes with high stakes and compelling, complex characters who are forced again and again to make uncomfortable choices between their own desires and saving the world.

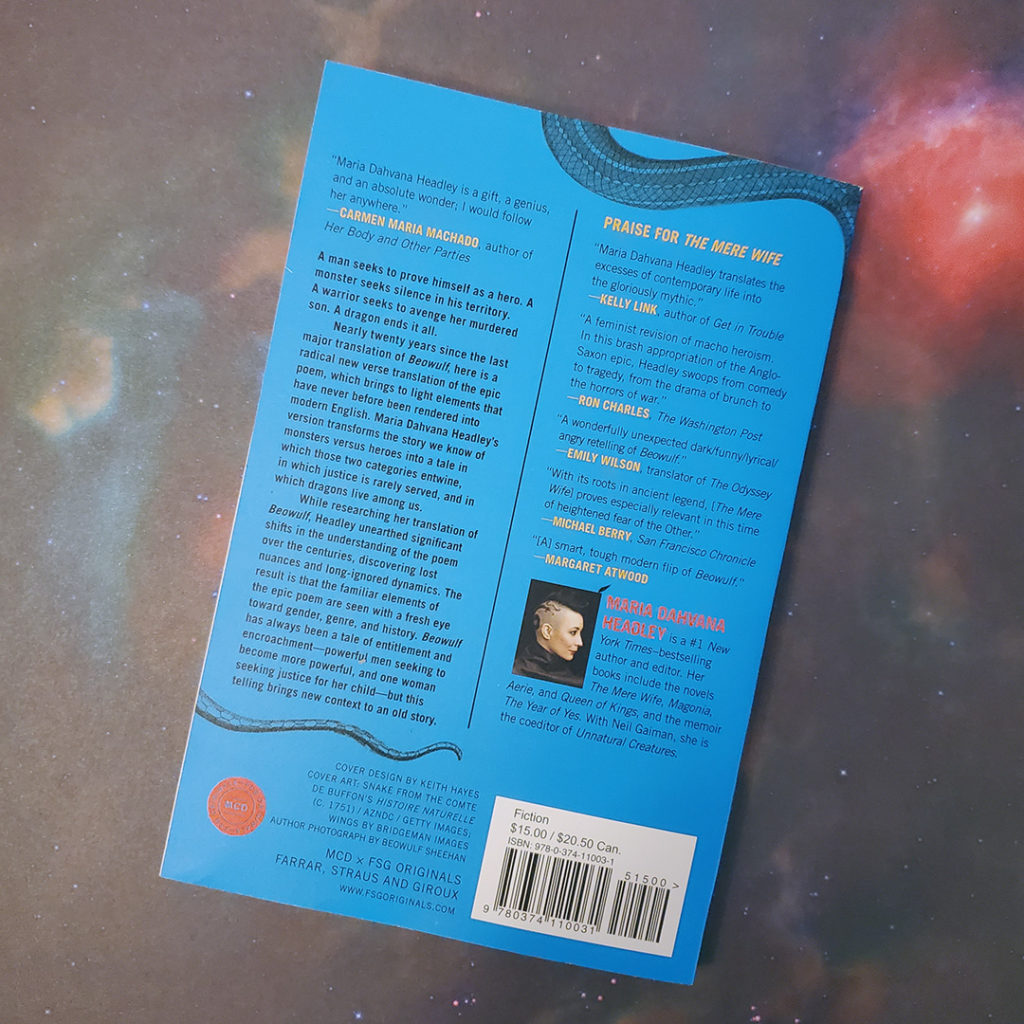

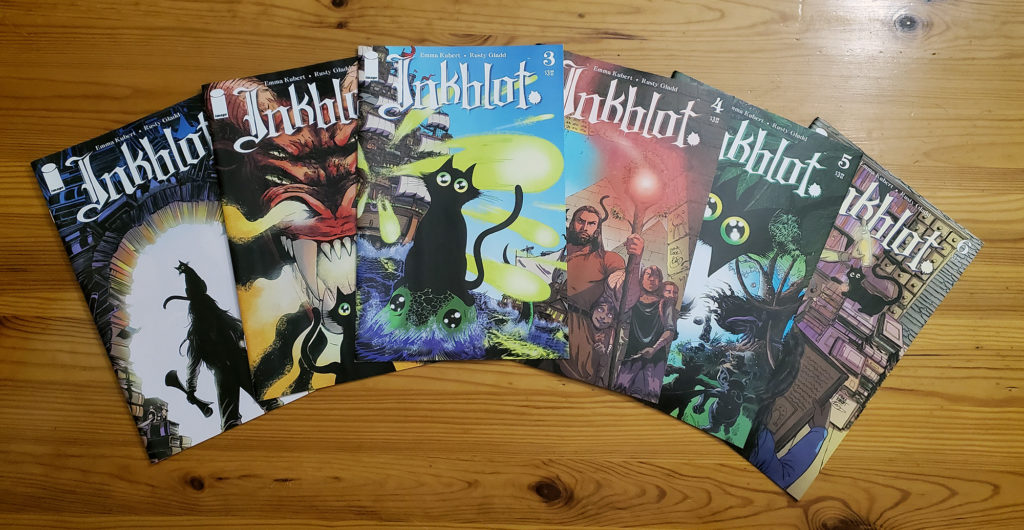

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this review, you may also enjoy my review of Inkblot by Emma Kubert and Rusty Gladd. I’d love to hear about what you’re reading currently on Instagram, Threads, or Bluesky!