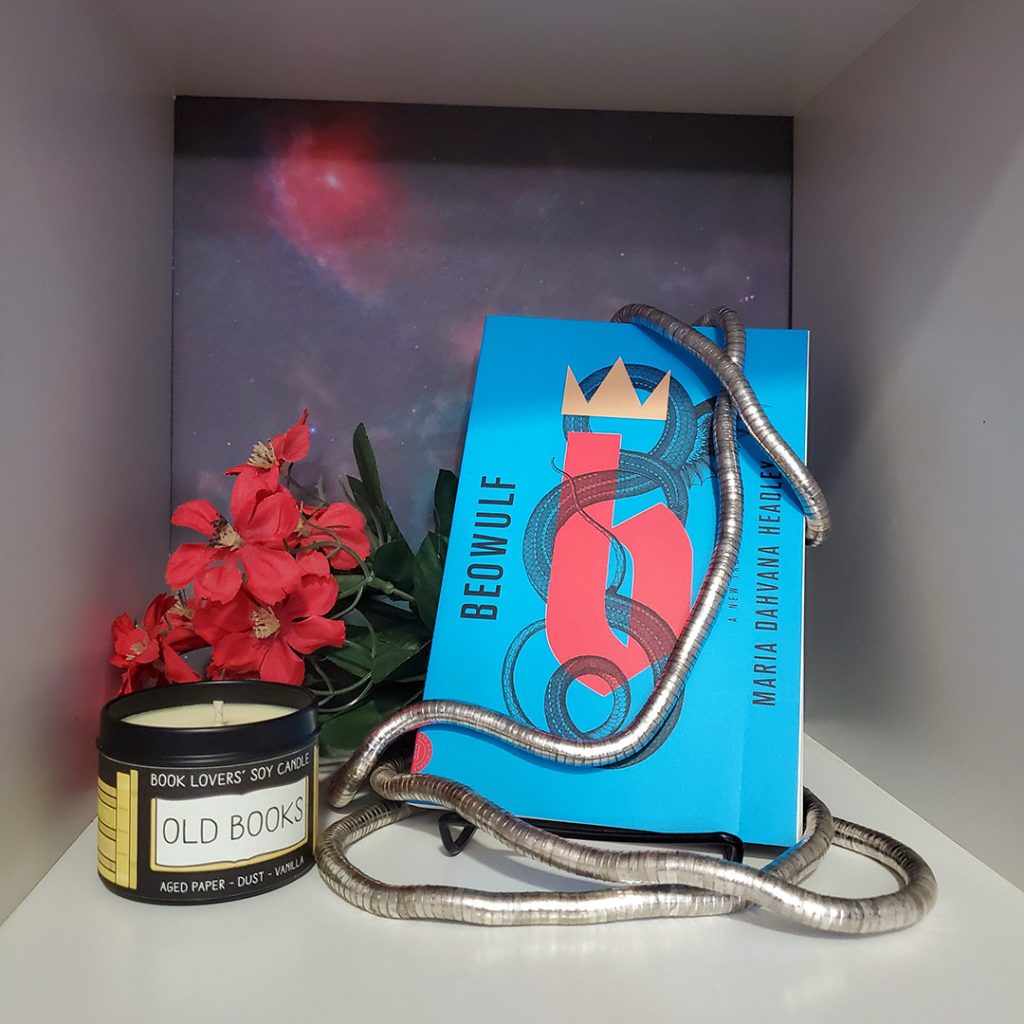

This week’s review covers Maria Dhavana Headley’s new translation of the Old English epic poem Beowulf. My reviews do contain affiliate links to Bookshop.org, an online bookstore that financially supports local independent bookstores.

I hesitated to review this book, as it’s been covered by folks much more knowledgeable about Beowulf than I in all sorts of prestigious publications (the New Yorker, NPR, Vox, just to name a few), but April is National Poetry Month, and I decided to forge ahead.

Reading Beowulf for the First Time

I first read Beowulf when I was in ninth grade, but not because it was an assigned reading. As a bookish, nerdy fourteen year old, I had taken it upon myself to read all the classics in science fiction and fantasy.

I can’t remember how or why I decided to start with Beowulf—perhaps because it was the oldest, perhaps because my father had mentioned that it had a dragon—but I picked up a copy from my local library and commenced reading.

It was 2001, and although I didn’t know anything about translations, I happened to select Seamus Heaney’s then-still-new version because it featured the Old English alongside the translation. The cover struck me even then: The silver chainmail against a stark black background.

I do remember that I finished reading Beowulf for the first time on the bus ride to school. It was early in the year still, summer hot and weeks away from September 11. It was my first year in public school after spending most of elementary and all of middle school in two separate Christian schools, and I didn’t yet have any friends, except of course, books.

I was confused, when I finished reading, because I had thought reading Beowulf was supposed to be awful. Boring. A slog. Impenetrable. But I loved it. Not just the story of triumph over Grendel and his mother, not just the fighting and the blood and guts and glory, but the language, the cadence of the sentences, the rhythm.

I carried the book around until I had to return it to the library, pouring over the Old English, comparing it to the new, reading the footnotes, reliving the action. When my English teachers failed to assign it in any of my classes throughout high school, I was actually disappointed.

Reading Beowulf: A New Translation

Twenty years out from my first reading of Beowulf, Maria Dhavana Headley graced the world with her version of the epic poem. Being a woman in the world of literature and acutely aware of the gender bias that persists even still, I was excited to have a woman translating one of my favorite classics.

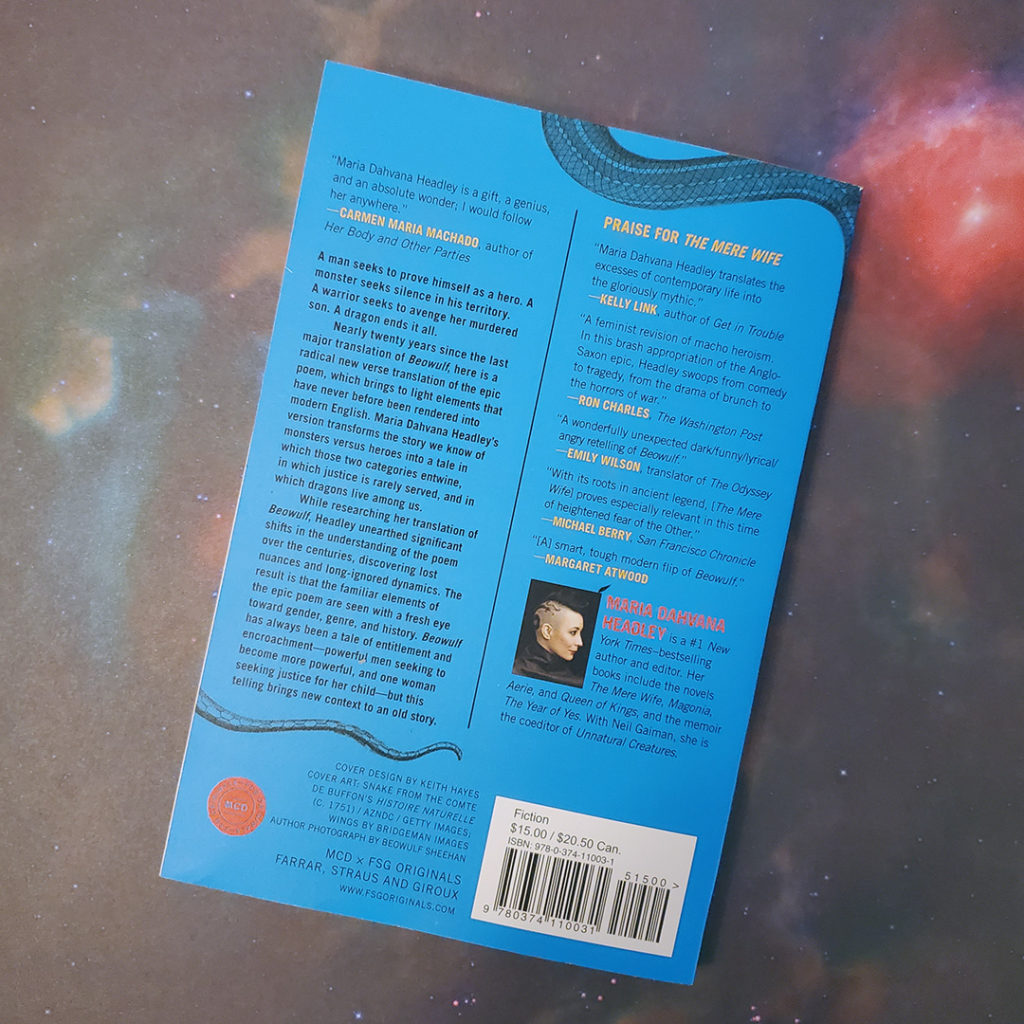

And my word, she does not disappoint. This book is worth buying for her introduction alone, where she challenges the long-standing assumption that Grendel’s mother must be a literal monster because of her sword fighting prowess, ponders the various dilemmas that crop up for any translator, and ultimately reveals the sheer weight of her love and enthusiasm for this story.

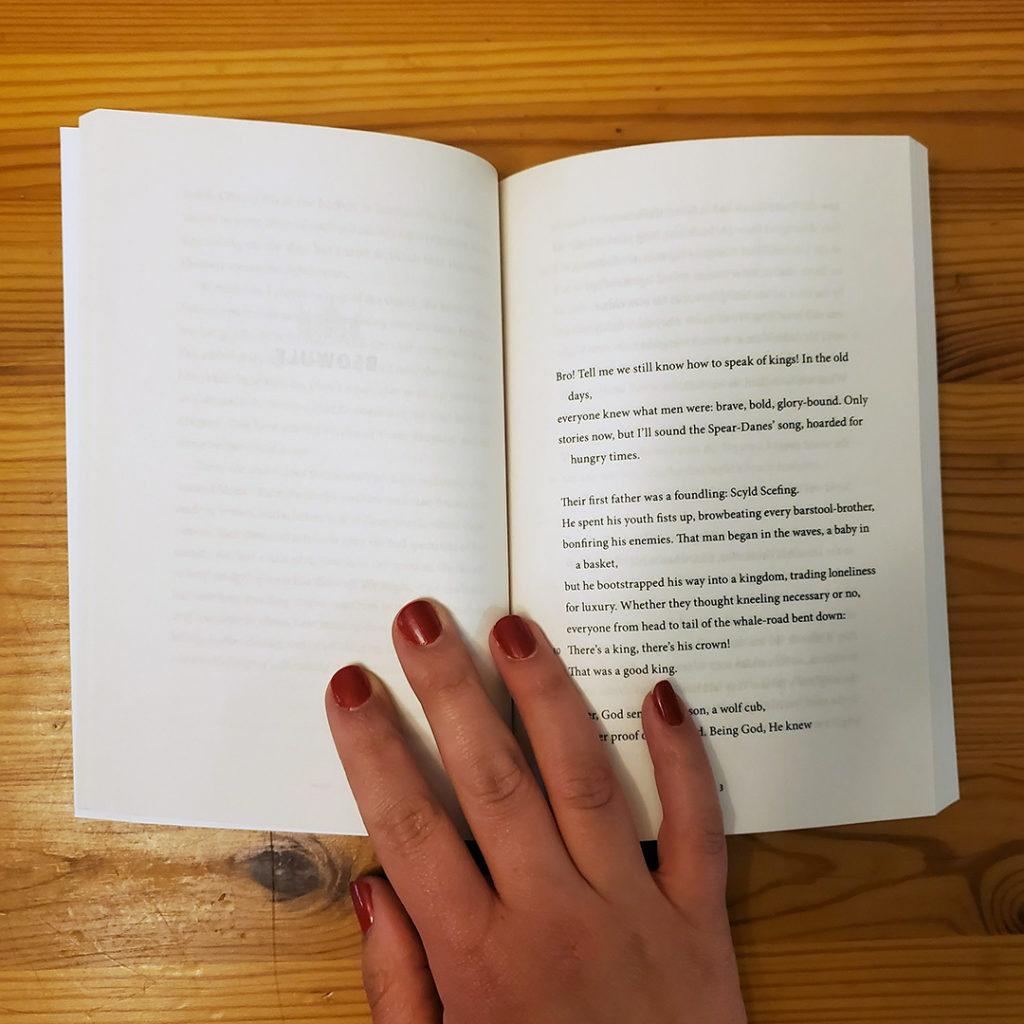

Headley’s translation brings the language of Beowulf into the twenty-first century while maintaining the old world feel of the story. I’ve seen some commenters dismiss her translation because it makes ample use of slang such as “bro,” but this, I think, misses the point.

This translation of Beowulf will endure for the same reason ‘90s film adaptations of Shakespeare’s plays, like Clueless and Ten Things I Hate About You, have endured: They touch on the universal by using the specifics of the moment, and use the specifics of the moment to add nuance and more layers of meaning to the original stories.

But to me, the real value of Headley’s translation is the way she uses it to challenge assumptions and reframe elements of the narrative. If Grendel was half-man, half-monster, why assume his mother was the monster and not his absent father? This is a question Headley explored at length in her novel about Grendel’s mother, The Mere Wife, but seeing the battle between Beowulf and Grendel’s human mother was a balm I didn’t know my soul needed.

Headley gives Grendel’s mother the space to be her complex self: a grieving mother, a capable swordswoman, and a villain in her own right.

Even setting this fresh interpretation of the only significant female character in the epic poem aside, Headley’s use of language, rhythm, and tone is nothing short of transcendent. Reading her verse is a joy; reading it aloud even more so. It’s fun, and it feels good on the tongue and lips.

Fans of Beowulf will enjoy this new translation, and even better, it will provide a new access point for readers who may never have discovered it or been interested in otherwise.

The Book Witch’s One Sentence Review

Maria Dhavana Headley’s Beowulf: A New Translation is fresh, fun, and challenges the reader to reassess long standing assumptions about the story and characters while remaining true to the epic spirit of the narrative.

Who’s your favorite queer speculative author? Let me know in the comments, on Twitter @bookwitchblog, or Instagram @bookwitchblog!